Canadian mining company to make another run at exploration for the potential and controversial CuMo Project open-pit mine

After water from Grimes Creek splashes out of the high country northwest of Idaho City and swirls into Mores Creek by Highway 21, it eventually meanders through Boise and the Treasure Valley in the Boise River all the way to the Snake River.

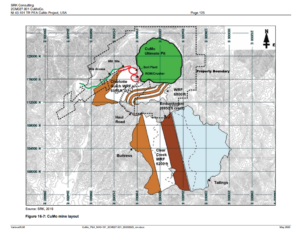

In the highlands between Charlotte Gulch and Grimes Creek, Canadian-based mining company Idaho Copper is hoping to gain approval from the Forest Service to construct up to 13.3 miles of new roads and drill 259 holes up to 3,000 feet deep for a mining exploration project. This project, called the CuMo Mine Exploration Project, is hoping to find sufficient copper (Cu) and molybdenum (Mo) to justify one of the largest open-pit mines in the world – all within the precious Boise River watershed.

In 2011, Canadian mining company Mosquito Gold proposed an extensive drilling plan in the mountainous area in the headwaters of Grimes Creek. Local and downstream communities were alarmed as mining is the number one polluter in the United States and even mining exploration can have adverse impacts. The Boise River is a precious resource – it provides more than 25% of Boise’s drinking water supply and helps irrigate over 300,000 acres of cropland.

Concerned about local impacts and negative effects to downstream uses, the Idaho Conservation League, Idaho Rivers United, and Golden Eagle Audubon previously challenged the mine exploration permit in federal court, represented by Advocates for the West and the Western Mining Action Project. In 2012, a federal court ruled that the Forest Service had failed to properly consider potential impacts to groundwater from drilling activities, and the decision was withdrawn. In 2015, the mining company (under the new name CuMoCo) tried again, but the court determined that the Forest Service had failed to conduct the required baseline environmental study for Sacajawea’s bitterroot, a rare plant that has a stronghold in the exploration area. The decision was once again withdrawn.

Encouraged by recent increases in metals prices, and with hopes that molybdenum (which is used to harden steel) will one day replace cobalt as a component of electric car batteries, the mining company (under the new name Idaho Copper) is once again proposing to restart drilling operations. In the coming weeks, the Forest Service is expected to release a “Supplemental Redline Environmental Assessment” with a revised proposal. Anticipated concerns with the newest exploration proposal include transportation of diesel fuel on narrow riverside and mountain roads and impacts of road construction and 24/7 drilling operations on wildlife and recreationists.

Of even greater concern is the mining company’s ultimate vision for this area as portrayed in the 2020 Preliminary Economic Analysis, which includes a 3,500 feet deep open pit:

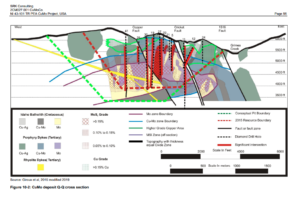

“The CuMo open pit is envisioned to be a large, deep pit (up to 3500 ft deep). With this comes the potential geotechnical risk for wall failures. While the author has assumed a relatively flat overall wall angle for the PEA (37°), there may be risks associated with yet unknown rock mass or structural geology conditions that may require consideration of even flatter slopes in places.”

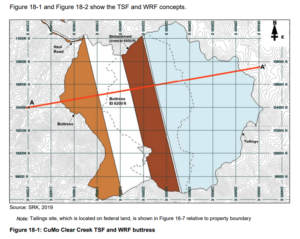

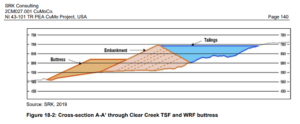

Another significant feature would be a new approximately 800’ high and 10,000′ wide storage facility across Clear Creek just south of Charlotte Gulch to hold mine tailings:

“The tailings storage facility (TSF) will be located at the headwaters of the Clear Creek watershed, in a natural basin formed by the surrounding ridgeline. The TSF will have capacity to store the 1,582M tons (~900M m3) of tailings produced over the 28 year mine life, with an ultimate crest elevation of 6,950 ft.”

The tailings facility would be built upstream of Pioneerville, Centerville, and New Centerville and would bury Forest Road 380 which connects Pioneerville to Coulter Summit. Poorly engineered and managed tailings storage facilities have failed with catastrophic consequences.

Idaho Copper appears to dismiss their proposed changes to the character of the landscape by describing the area as “heavily mined and logged over the past 100 years”:

“[T]ailings, waste dumps and the deposit footprint are relatively small compared to the area of existing disturbance. In fact, the project development should lead to an overall improvement in the environment rather than degradation.”

The reference to “the area of existing disturbance” has caused some confusion. While the lower stretches of Grimes Creek and Mores Creek have been heavily impacted by historic mining activities, the area is now completely reforested, watershed restoration projects have been going on for years, and the forested landscape is of incredible value to many. It is unclear how a massive open-pit mine complex would improve the area.

Another issue identified in the Preliminary Economic Assessment is water use:

“Fresh water supply from surface or ground water will likely be one of the most difficult hurdles to overcome. An estimated 30,000 gpm of fresh water could be required…The project will be located in Basin 65 which includes the entire Boise River Drainage (IDWR, 2018). P. 150.” Preliminary Economic Assessment p. 150

Aside from environmental issues, the Preliminary Assessment Report notes that there could be challenging social changes as well:

“Potential social issues that could arise from the CuMo project could generally include:

- A shortage of temporary and permanent housing

- Insufficient of capacity of schools, health care, law enforcement, solid waste disposal, and municipal infrastructure

- Insufficient road network capacity leading to traffic slowdowns and degradation of road surfaces

- Increases in crime, drug abuse, and alcoholism” (Preliminary Economic Assessment p. 149)

Although the open pit mine plan is a draft proposal at this time, such a mine would pose an existential risk to the Boise River watershed. Community members need to be aware of the current and future threats before the project is permitted. Allowing the exploration project to proceed as proposed is the equivalent of the camel putting its nose under the tent.

The Forest Service previously held public meetings on the exploration plan in Garden Valley, Idaho City, and Boise. We believe that the issues regarding water quality, recreation, traffic, public safety, and wildlife are even more important today than they were in 2011.

We Are the Boise River from Idaho Conservation League on Vimeo.

Under the Mining Law of 1872, the Forest Service cannot deny the project but can work to reduce the impacts. The Forest Service will be hosting public meetings about this proposal. These meetings are important ways for members of the public to learn more about the latest exploration proposal, share their expertise and concerns, and recommend additional ways to avoid, minimize and mitigate impacts.

In regards to molybdenum, there are already discussions about restarting mining the mineral at the Thompson Creek Mine near Challis, which is an existing, permitted open-pit mine. We believe that Idaho should have one large-scale open-pit molybdenum mine at a time, and none upstream of the Treasure Valley’s drinking and irrigation water supply.

To learn about ways to speak up for the Boise River against this proposal, sign up for our Public Lands Campaign email updates below or just text IDAHO NOCUMO to 52886.