Recent research by the U.S. Department of the Interior showed that the construction and continued operation of the Federal Columbia River Power System (FCRPS) – the set of 31 federal dams operating on the Columbia River and its tributaries – has fundamentally changed the function of these rivers. Beyond altering the complex hydrology and ecology of the region, the dams effectively stole billions of dollars and an invaluable cultural resource from Tribes, and transferred it to other industries, which now reap the benefits of the system of dams through power production, commodity transportation, flatwater recreation, and agricultural irrigation.

The Department’s “History and Ongoing Impacts of Federal Dams on the Columbia River Basin Tribes” is a brief summation of this thievery. Here are some of the overarching themes of the report.

Tribes have an ancient, deep connection with Northwest rivers

Since time immemorial, Columbia Basin Tribes based their culture, economy, and seasonal movements on the bounty provided to them by the Columbia River and its tributaries. This culminated in regular gatherings of dozens of Tribes at the great centers of the Northwest: Celilo Falls (near The Dalles, Oregon) and Kettle Falls (near Spokane, Washington). Here, peoples from across the region would hunt salmon from the river, engage in trade, and celebrate together.

For at least fourteen hundred generations, my family and my people traveled to Celilo to harvest the salmon we needed in order to maintain our life and our culture. Celilo was the center of our salmon culture and our traditional economy.

While land territory was hugely important to Tribes, they recognized that the true wealth of the region wasn’t in the land itself, but in the fish, game, and fruits that came from it.

As Yakama Chief Meninock testified: God created this Indian country and it was like He spread out a big blanket. …When we were created we were given our ground to live on, and from that time these were our rights. This is all true. …My strength is from the fish; my blood is from the fish, from the roots and the berries. The fish and the game are the essence of my life.

When it came time to make Treaties with the US Government, Tribes thus prioritized reserving their access to these resources. They protected the right to hunt fish and wildlife and to gather at “usual and accustomed places.”

Tribes generally retained hunting, fishing, and gathering rights that continued their connection to the resources that were culturally and physically important to them. Reservations created under the treaty-making process were retained as part of the Tribes’ inherent rights to the land and resources that the Tribes reserved, along with all other rights or privileges not expressly ceded in the treaties.

These reserved rights were fundamental to the Tribal representatives’ willingness to sign the treaties and limit their lands to reservations. Because the treaties and reservations massively reduced the Tribes’ territories, the Tribes understood that retaining these rights “was essential to their material and cultural survival.”

Construction of federal dams robbed Tribes of their resources

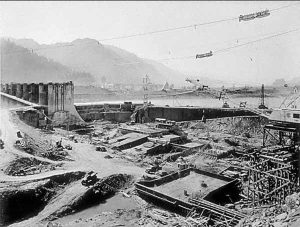

The federal government started building large dams on the Columbia River in 1934, when construction on Bonneville Dam (near Portland, Oregon) and Grand Coulee Dam (in central Washington) commenced. Immediately, fish populations in the river started to decline.

Celilo Falls, the longest continually-inhabited community in North America (more than 15,000 years), was swallowed up by the waters trapped behind The Dalles dam, which was finished in 1957. The US Government forcibly removed Tribal members from Celilo Village, whose protection had been guaranteed to Tribes as a central fishing site. Little consideration was given to Celilo as an irreplaceable cultural property.

The only consideration given to Celilo Falls, another area of indescribable importance to the Yakama Nation, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Warm Springs Tribes, was to recognize it as a “major obstacle to navigation.”

Indeed, some bureaucrats saw a benefit to the removal of Celilo, believing that its loss would allow more fish to survive.

Emblematic of the government’s lack of concern for this result, one federal representative separately asserted that “drown[ing] out the Indian Celilo fishing sites” would “be an important boon to fish conservation.”

And, that robbery wasn’t accidental

Though not covered in the Tribal Circumstances Analysis, other research by journalists at ProPublica shows a well-documented intent by government officials to use dams to stamp out Native American Tribes and their culture by destroying Tribal salmon fisheries. A trove of federal documents exhibits disturbing statements from officials who knew exactly what consequences the building of dams would have on Tribal Nations.

The documents reveal that the government’s 1950s era of dam building on the Columbia was marked not by a failure to consider tribal impacts, but rather by a well-informed and intentional disregard for Native people.

The presence of Native Americans and protected status of their fisheries were seen as a problem and a barrier to non-Tribal fisheries and industry. Dam building and flooding of ancient cultural sites, such as those at Celilo and Kettle Falls, was an easy way to remove this barrier.

The head of the Port of Vancouver at the time, Frank Pender, also told federal officials of “the Indian problem” and said of tribal fishing, “certainly we don’t want it to stand in the way of the development of our own way of life.”

Tribal members interviewed by the ProPublica team acknowledge this as an attempt at cultural genocide, readily comparing the massacre of salmon by dams to the massacre of millions of American bison that happened on the Great Plains in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“It was kind of like what happened to the buffalo,” Settler told OPB and ProPublica during the initial reporting for “Salmon Wars.” “If they could rid the natural food of those tribes that they were dependent upon, they could weaken the tribes and get them to stop going across their ancestral territories. They would be more confined to their reservation lands where they could be controlled.”

Tribal members immediately recognized what was happening and attempted to raise the alarm with state and federal agencies and officials.

Tribal fishermen quickly noticed and made known the impact on salmon, calling attention to changed behaviors, thermal alterations, and passage-related mortality, among other concerns. As early as 1937–38, given the severity of the impacts observed, the Tribal fishermen predicted a loss of all salmon.

These calls were largely ignored until the 1980s, when the decline in salmon populations had progressed so far that even non-Tribal fishers could no longer depend on the availability of fish to catch. This prompted the enactment of the Pacific Northwest Electric Power Planning and Conservation Act in 1980, which sought to avoid fish stocks being listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

That didn’t work. Snake River coho went extinct. Snake River sockeye salmon became the first Northwest fish population listed under ESA in 1991, followed by a dozen more stocks across the region. Since their listing, most of these wild stocks have not significantly improved.

Previous federal actions to remedy the situation have not worked

Even as wild fish have failed to recover, federal agencies sunk billions of dollars into a system of hatcheries intended to produce fish available for Tribal and non-Tribal harvest. The Tribal Circumstances Analysis goes in depth on the failures of this system.

Many of the hatchery programs have not met their identified mitigation responsibilities: the Lower Snake River Compensation Plan spring Chinook mitigation objective has not been met, nor has the John Day mitigation objective. Recent abundance goal setting has relied on “interim goals” out of acknowledgement that decades of implementation have yet to generate actual fishery abundance in the Basin. The failure to meet abundance goals contributes to salmon harvest deficits. At no point since the beginning of Columbia River Basin development have Tribal fishers been able to harvest more than a fraction of their historic share of salmon returns. Additionally, the hatchery programs have not received adequate annual operation and maintenance funding, and maintenance and infrastructure upgrades for hatcheries has been deferred—in contrast to maintenance and infrastructure upgrades at the dams (e.g., turbines).

ProPublica has also documented this widespread failure.

By the late 1970s, hatcheries were releasing three times more juvenile salmon than scientists estimate the wild fish ever produced themselves. But fish counts at federal dams showed that while tens of millions more juvenile salmon were heading downriver each year, the number of returning adult salmon kept dropping.

Hatcheries remain important to create any kind of fishing season, since it is largely illegal to harvest ESA-listed wild salmon and steelhead, but the lack of investment in hatcheries has ensured that they will never attain their original goals to mitigate the impact of the federal hydrosystem.

Injustice continues

As long as the federal dams remain in place and salmon aren’t available to Tribes, injustice remains. Promises stay broken, and the connection between Tribal members and their cultural foundations becomes thinner, generation by generation.

Every day this situation persists makes the Tribes’ cultural link to the salmon and these places harder to maintain. This loss of connection to fishing places is felt whether it results from inundation, by the reshaping of the hydrograph and river, or the impacts to juvenile and adult salmon as they migrate through the hydrosystem.

Beyond fish, there are significant historic Tribal properties and relics inundated by the reservoirs behind federal dams. In a remarkable logical leap, the US Army Corps of Engineers has claimed that the sites are thus protected under feet of water. The report shows how ridiculous that notion is.

The Nez Perce note that to suggest inundation of the lower Snake River protects cultural resources by keeping them covered by water does not account for the fact that the Tribe’s culture depends on the salmon and the life source of the lower Snake River. Additionally, the reservoirs’ existence and constant inundation of other sites and properties effectively means unending damage to those resources, and for those locations that are not permanently destroyed by the water, prohibition of access by Tribal members.

The system of dams creates unending damage on Tribes and their resources, until something fundamentally changes.

What’s the pathway forward?

The Tribal Circumstances Analysis was conducted as part of the Resilient Columbia Basin Agreement, a landmark set of commitments by the federal government to Northwest states, Tribes, and conservation organizations. This agreement lays out the first steps of a pathway to restoring truly abundant salmon and steelhead throughout the Columbia Basin. The Department of the Interior’s report will be used as a basis for all federal analysis going forward that evaluates the effects of the dams on Tribes.

The report’s admission of these historic wrongs is significant. The US Government is essentially confessing that its past practices were unjust. But the pathway to addressing those harms and undoing those practices is less clear. First, federal agencies must push ahead on a set of studies that evaluate how to replace the services of the lower Snake River dams, so that those dams can be breached. Concurrently, federal agencies must evaluate and fund other salmon restoration programs in the region, including habitat work in the Mid-Columbia, hatchery improvements, and reintroduction of fish into the Upper Columbia River.

The report’s publication is a small step toward a future of abundant fish and restored Tribal rights to those fish. That’s more than an abstract concept: it has real, concrete consequences for Tribal members, their families, and the next generations.

From the report:

In sum, there’s a huge connection between salmon and [T]ribal health. Restoring salmon restores a way of life. It restores physical activity. It restores mental health. It improves nutrition and thus restores physical health. It restores a traditional food source, which as we know, isn’t everything– but it’s a big deal. It allows families to share time together and build connections between family members. It passes on traditions that are being lost. If the salmon came back, these positive changes would start.