Editor’s Note: This post was co-authored by ICL’s Wildlife Program Associate Jeff Abrams and Public Lands Director John Robison.

The Snake River, just about halfway between its beginnings near Palisades Reservoir and the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area, bows southward near Twin Falls, like one gargantuan volcanic smile spanning the entire state of Idaho. Along the right half of the grin, the river cuts through an area known as the Eastern Snake River Basalt Plains.

This swath of southern Idaho has hosted all manner of animals going back to the Ice Age, as camels and short-faced bears commingled with the mule deer and pronghorn that still occupy the landscape today. Those familiar animals are linkages to the Pleistocene days, providing testimony to this consistently rich and biologically diverse landscape.

While this cradle of lava remains generally fertile for wildlife, much of the environment has been altered over the last 150 years, particularly with construction of large-scale irrigation projects, which settlers used to “make the desert bloom.” Today, a complex matrix of human impacts conspires to make the area an increasingly difficult place to scratch out a living for everything from birds and bats to tiger beetles and monarch butterflies. Landscape alterations have come from agriculture and grazing practices, invasions of nonnative plants, construction of roads and ORV/OHV trails, rights-of-way, residential development and large-scale wildfire events resulting from climate change.

Despite these changes, in many ways, terrestrial and avian species seem to be modestly adapting to the increasing suite of difficulties. Pronghorn migration routes still wind sinuously through a maze of buttes and ravines, leading from summer to winter ranges and back. Hunting for mice and voles is still profitable for the buff-brown ferruginous hawk. Pollinators, like bumble bees, continue to carry out their vital role in plant communities. Wildlife is still persisting.

However, a proposal for the largest wind power generation facility in the country, Lava Ridge, now prompts the question of how much more alteration can occur before conditions are so unnatural that ecosystems don’t function properly anymore and can’t meet the needs of their occupants. At what point is disturbance just too significant that it becomes insurmountable for some species? That’s what ICL is diligently examining right now, during a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) public comment period for the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) associated with this commercial proposal by LS Power (via Magic Valley Energy subsidiary). Comments are due by April 20, 2023.

As currently configured, the project would sit mostly on BLM lands, roughly 20 miles to the northeast of Twin Falls. Project construction, operation, and decommissioning would last an estimated 34 years, and another 50 years would be needed to complete reclamation measures. Under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the BLM has primary review and permitting authority over the proposal, which, after evaluating five different Alternatives prior to the release of the DEIS, has chosen two Alternatives – C and E. While the range of options originally accounted for up to 400 towers and turbines covering around 85,000 acres, Alternatives C and E have decreased those ambitions by roughly 35-45%. However, many fundamental issues with the larger-scale Alternatives are still significantly present, though to lesser degrees, in the BLM’s two preferred options.

As large as ground disturbance to tens of thousands of acres seems, impacts of the proposal for some species using this landscape would extend for miles in all directions. Additionally, at least three other alternative energy proposals near Lava Ridge are also in various phases of planning. This means that the BLM must consider not just local effects on wildlife, but cumulative impacts of “future events” that may cause harm, over time, to an entire population of animals. Those could include impacts to population viability, population connectivity, migration connectivity, displacement, and direct mortality to individuals.

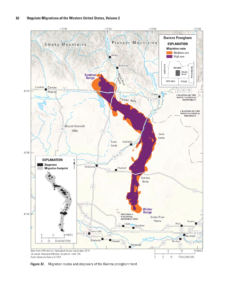

For some species like bats, the rapid expansion of wind power in inappropriate areas is one the biggest threats to their continued persistence. Eagles are known to abandon nesting sites if human-sourced noise disturbance is too significant. For pronghorn and mule deer, two Priority Areas identified as part of a Department of Interior Secretarial Order (SO 3362) for winter range and migration paths are in the BLM’s Lava Ridge analysis area. Many species in the area have been designated with a special level of conservation status by the BLM (Sensitive Species of Special Concern) and the State of Idaho (Species of Greatest Conservation Need as listed in the Statewide Wildlife Action Plan). Several other species potentially affected by the proposal, like the greater sage-grouse, are being considered for federal protection. Lava Ridge successfully avoids the most important habitat for greater sage-grouse, but ideally renewable energy projects would avoid sage-grouse habitat entirely.

Here’s a summary of “who’s who” up on Lava Ridge and a few concerns relating to each of them:

- Wild Ungulates: pronghorn, mule deer and elk (roads, fences, migration routes/stopover areas, noise, human presence, etc.)

- Avian Predators: golden eagle, bald eagle, ferruginous hawk (tower/turbine/guy wire strikes, noise, etc.)

- Other Birds (up to 45 species): examples are greater sage-grouse, long-billed curlew, burrowing owl, short-eared owl (habitat degradation, ground disturbance, noise, human presence, increased predation, etc.)

- Bats: hoary, silver-haired, big-eared, little brown, big brown (tower/turbine/guy wire strikes, etc.)

- Pygmy rabbits (habitat degradation)

- Pollinators & Insects: tiger beetle, monarch butterfly, bumble bees

For many species, there is little specific information available on effects of wind power development – only that they avoid industrialized habitats and don’t habituate to human presence. However, it’s clear that the project, as described in the DEIS, would represent a major disruption to lots of wildlife that calls the area near Lava Ridge home. Some animals with small home ranges may experience long-term displacement from construction and operation disturbance. Many will be unable to relocate due to new sections of degraded habitat and physical barriers to movement.

At the same time, if we don’t take bold action to reduce the impacts of climate change and transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, many of these same species we care about will be worse off. The last five years were the hottest on record, and wildfire seasons in Idaho are now 80 days longer than they used to be.

For example, if we fail to reverse climate change, almost all sage-grouse in all of southern Idaho are projected to be extirpated. The size of the surviving remnant sage-grouse populations in the mountain valleys will be determined by how quickly we address climate change. The Audubon Society has created a model showing this decline under different warming scenarios. Scroll down to the section, “How Climate Change Will Reshape the Range of the Greater Sage-Grouse.” Right now, our society is blowing past the 1.5 degree Celsius mark, which does not bode well.

In short, we cannot pretend that our way of life is going to stay the same if we don’t add renewable energy projects:

“If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

― Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, The Leopard

This brings us back to Lava Ridge. Out of the four action alternatives, none of them appear to strike the right balance of advancing America’s clean energy goals while also protecting the public land and wildlife values in the area of development. Even if there is an alternative that addresses wildlife issues, the impacts to cultural and historic features may still not be acceptable.

ICL has a three-step approach to Lava Ridge:

- ICL will be asking the BLM to see if a new alternative can better avoid, minimize, and mitigate wildlife impacts. In terms of avoiding impacts, the BLM has not assessed an alternative that avoids both pronghorn and sage-grouse habitat. For minimizing impacts, we would like to see the turbines curtailed during high periods of bad migration. For mitigating impacts, we would like to see a comprehensive effort to remove barriers to pronghorn migration in nearby areas and improve habitat for sage-grouse.

- For portions of the Project Area that contain valuable wildlife habitat and important Tribal and Cultural Resources that are deemed not suitable for renewable energy projects, ICL will be asking the BLM to amend the Resource Management Plan to ensure these areas are safeguarded and prioritized for habitat restoration and protection. The BLM and partner organizations are not likely to invest in habitat restoration work for areas that remain available for renewable energy developments.

- We are asking the BLM to take a more comprehensive look across all of southern Idaho to see which areas are and are not appropriate for large-scale renewable energy development. There may well be other sites that have fewer wildlife and cultural issues than Lava Ridge, but we won’t know until we take a programmatic look. Public input will also be critically important in ensuring we don’t end up trying to place the wrong project in the wrong place.

Please weigh in with your own comments by April 20, 2023.