It’s a brisk early summer morning. The line of cars grows as motorists pause, pay their fee, and receive a visitor map at the kiosks near the stone archway marking the grand, north entrance to Yellowstone National Park. The ranger’s greeting quickly fades from memory as the jaw-dropping landscape unfurls before the bug-streaked windshields of travelers. They’ve arrived from every corner of the planet. Mammoth Hot Springs, Sepulcher Mountain, and the distant Absaroka Range are the first to stun with geologic grandeur. A thick carpet of green is laid out in the glacially carved valley spaces between craggy ridgelines. Yet, even with all of the surrounding majesty, the showstopper often comes in a different form.

This year, the wonders of Yellowstone will likely attract over 4.5 million people. Undoubtedly, each will have their own gawker’s checklist. Maybe Old Faithful takes top bill or a mama grizzly with a gaggle of rambunctious cubs. Or, maybe…..the spectacle has horns and hoofs.

For many, the most unique and highly anticipated of all opportunities presented by the Park is the potential to witness an American bison in person. Months of planning and summer vacation preparations are often animated by the alluring prospect of seeing the 2,000-pound bovine embodiment of America The Beautiful.

And that instance—when one comes mere car lengths from the biggest land mammal in North America—can be profound. It forces one into somehow trying to reconcile the unfathomable reality that, 150 years ago, our country came within a whisker of losing this icon of native North American wildlife. Tens of millions of animals once ranged from the middle of Oregon to Appalachia and Mexico to west central Canada. By the 1880s, there were a few hundred.

Nowadays, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is home to roughly 5,000 bison. There is no other place on the planet to watch bison on this natural, majestic scale. The population has been studied perhaps as much as any other native mammal in the world. A new National Park Service management plan for bison has just been finalized, creating an opportunity to deepen our national relationship with this keystone species and cultural totem for many Native peoples. Overwhelming public input encouraged the Park Service and the State of Montana to manage bison more like deer and elk that range far and wide, unencumbered by National Park boundaries. Those sentiments could serve as a springboard for our region to have more substantive conversations about allowing bison to re-occupy historically significant landscapes within and adjacent to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Nevertheless, Montana is threatening to sue the National Park Service over the bison plan.

America’s shared bison experience should not be relegated to the boundaries of Yellowstone National Park. We deserve more. So do bison. While visitors delight in incredible watchable wildlife experiences and the latest management plan provides for wider opportunities for Tribal harvest and conservation actions, America’s collective engagement with our national mammal should be happening on a much broader scale. This evolution is also important for the biological benefits bison bring to arid western landscapes.

Important grassland and shrub-steppe landscapes of the west are increasingly threatened from invasive plants, large-scale fire, agricultural conversion and development. Over 50 million acres of this indispensable habitat type has been lost in the last decade. As highly adapted native grazers, bison are “biodiversity boosters,” helping retain moisture on public lands and assist in increasing local presence of avian, mammalian, and amphibian species. They are also well-suited to tolerate changing environmental conditions expected to come from climate change. Bison could serve as a critical lever to help restore significant chunks of the west if local communities were equipped with tools to embrace them as part of the wildlife landscape.

For all these reasons, the Idaho Conservation League wants to be part of a discussion about roadmapping a future with bison beyond the confines of Yellowstone.

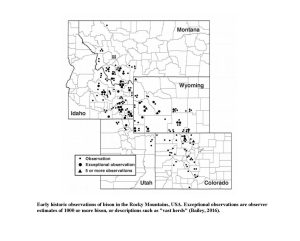

James Bailey’s American Plains Bison: Rewilding an Icon offers historic accounts by western trappers like Osborne Russell that put thousands of bison in intermountain valleys, alpine grasslands, and forests between the Lewis and Clark route and places like Henry’s Lake, Dubois, Fort Hall, and other parts of southeast Idaho. Historical records from 1805-1845 indicate that bison were observed in at least 19 Idaho counties and herds in excess of 1,000 animals were documented on 17 occasions during that period. Productive bison habitat doesn’t necessarily have to appear as sublime as Yellowstone Park.

Prior to the grotesque overexploitation of bison as a commodity and a general US military strategy to subjugate and purge Native Americans from their homelands, herds occupied marginal habitat types, including forested areas, quite well. The Great Plains hosted a very large, core population of animals, that would make opportunistic use of movement corridors to disperse into adjacent areas to the west (known as the Western Cordillera) during milder seasons or with fewer human threats. Nevertheless, research has shown that bison were able to scratch out a living in many western landscapes that weren’t highly productive—with only moderate forage quality—where risks from human and large carnivore predation were relatively low.

While bison densities were lower than in the Great Plains region, history has shown that Idaho—especially areas in the eastern half of the state—hosted significant populations of bison. One main connectivity artery was the Snake River Plain in eastern Idaho, which broadly served to connect western lands of the Cordillera to the Green and Missouri River basins to the east. Numerous accounts of bison by trappers, missionaries, and military excursions were centered in and around this area, which generally spanned the continental divide. There, bison were observed in every month of the year. Many accounts placed bison in Idaho, even in winter months.

In many parts of the west, bison are slowly being allowed to reoccupy historic habitat—primarily through a diverse array of creative Tribal initiatives. ICL looks forward to understanding how these successes might be able to inspire conservation efforts across an even broader swath of western lands. Public comments on the Yellowstone bison plan clearly showed high levels of support for expansion of the animal’s range, provided thoughtful measures are taken to mitigate potential challenges, including conflicts with humans and livestock. Restoration of bison in carefully identified areas of Idaho will require a collective effort from a diverse set of stakeholders. However, over ICL’s 50-plus-year history, we’ve always believed that big, ambitious things are possible when effective advocacy aligns with well-timed opportunity. We think this may be just the case with bison making a return to Idaho.